In Everything Real and Imaginary There Is Art and Mathematics

Imaginary numbers are non imaginary at all. The truth is, they have had far more than affect on our lives than anything truly imaginary ever could. Without imaginary numbers, and the vital function they played in putting electricity into homes, factories, and internet server-farms, the modern globe would not be. Students who might complain to their math instructor that there's no indicate in anyone learning how to use imaginary numbers would take to put down their phone, turn off their music, and pull the wires out of their broadband router. But perhaps we should start with an explanation of what an imaginary number is.

Nosotros know by now how to square a number (multiply information technology by itself), and we know that negative numbers make a positive number when squared; a minus times a minus is a plus, remember? So (–2) × (–ii) = 4. Nosotros also know that taking a foursquare root is the inverse of squaring. Then the possible foursquare roots of 4 are 2 and –2. The imaginary number arises from asking what the square root of –four would be.

What we're discovering here is not some deep mystery about the universe.

Surely the question is meaningless? If you square a number, whether positive or negative, the answer is positive. And so y'all can't do the changed functioning if you showtime with a negative number. That's certainly what Heron of Alexandria seemed to think. Heron was the Egyptian architect whose mathematical tricks, written in Stereometrica, gave us the dome of the Hagia Sophia. In the same volume, he showed how to summate the book of a truncated square pyramid; that is, a pyramid with the meridian chopped off. His solution for one example involved subtracting 288 from 225 and finding the square root of the outcome. The event, though, is a negative number: –63. So the respond would be found via √–63.

For some reason—whether a sense that at that place was some mistake, or someone copied something down wrong, or because information technology was so cool—the manuscripts we have show that Heron ignored the minus sign and gave the respond every bit √63 instead.

The square roots of negative numbers are what we now call imaginary numbers. The first person to suggest that they shouldn't exist ignored was the 16th-century Italian astrologer Jerome Cardano, who was embarked on a k project: a book detailing all of the algebraic cognition of his times. While working out cubic equations, he stopped and stared at the effect. At first, he called them "incommunicable cases." In his 1545 book on algebra, The Great Art, he gave the example of trying to divide 10 into two numbers that multiply together to make 40. In the process of finding those numbers, you come up beyond 5 + √–15.

Cardano didn't shy abroad from this unexpected encounter. In fact, he fifty-fifty jotted down a few thoughts almost information technology. Withal, he wrote in Latin, and translators fence well-nigh what he actually meant. For some, he calls it a "imitation position." For others, it's a "fictitious" number. Even so others say he characterizes the state of affairs as "impossible" to solve. One of his further comments on how to proceed in such a situation is translated every bit "putting aside the mental tortures" and every bit "the imaginary parts being lost." Elsewhere he refers to this as "arithmetic subtlety, the end of which … is as refined equally it is useless." He says it "truly is sophisticated … 1 cannot bear out the other operations one can in the case of a pure negative." By pure negative, he means a standard negative number, something like –4. He was happy with negative numbers and wrote that "√ix is either +3 or –3, for a plus [times a plus] or a minus times a minus yields a plus." And then he continued, "√–9 is neither +three or –3 just is some recondite 3rd sort of thing." Cardano conspicuously thought the foursquare roots of negative numbers were something abstruse and abstruse, merely at the same time he knew they were something—and something that a mathematician should appoint with. The task wasn't for him, though; none of Cardano'south subsequent writings mention the square roots of negative numbers. He left information technology to his fellow countryman, Rafael Bombelli, to accost them a couple of decades or then later.

In what he called a "wild thought," Bombelli suggested in 1572 that the two terms in v + √–15 could be treated as two carve up things. "The whole matter seemed to rest on sophistry rather than truth," he said, simply he did it anyway. And nosotros nevertheless do it today because it works.

A total mathematical description of nature requires imaginary numbers to exist.

Bombelli's two separate things were what we now telephone call real numbers and imaginary numbers. The combination of the two is known as a "complex number" (information technology'southward complex as in "military-industrial complex," speaking of combination—of real and imaginary parts—rather than complication). But let's be clear. If there'due south one thing we've learned in our time revisiting mathematics, it's that all numbers are imaginary. They are simply a note that helps with the concept of "how many." So applying the proper name "imaginary numbers" to the square roots of negative numbers is pejorative and unhelpful.

That said, we should admit a distinction. What mathematicians call "real" numbers are the numbers you're more than familiar with. The "2" in two apples; the 3.14… in pi; the fraction. And just as positive numbers are in a sense complemented past negative numbers, what we call existent numbers are complemented by what we at present have to telephone call imaginary numbers. Think of them as yin and yang, or heads and tails. And certainly not as actually imaginary.

Bombelli, in his wild idea, demonstrated that this new tribe of numbers accept a role to play in the real world. He set out to solve a cubic equation that Cardano had given up on: x3 = 15x + 4. Cardano's solution required him to deal with an expression that contained the foursquare root of –121, and he only didn't know where to go with it. Bombelli, on the other paw, thought he might try applying normal rules of arithmetic to the foursquare root. So, he said, maybe √–121 is the same as √121 × √–1, which gives 11 × √–1.

Bombelli'south corking breakthrough was to come across that these foreign, seemingly incommunicable numbers obey simple arithmetic rules once they are separated out from the other, more familiar types of number during a calculation. Everything after that was but grasping the nettle.

Proceeding with Cardano's cubic equation, he eventually arrived at a solution:

x = (two + √–1) + (2 – √–1)

Separate them out into what we would now call their real and imaginary parts, and it simplifies to 2 plus 2, and √–1 minus √–ane. The imaginary part disappears, leaving us with just two + 2. And so 10 = 4 is one of the solutions to xiii = 15x + 4. Plug it in and cheque for yourself.

These days, the convention is to employ i to represent √–one. The Swiss mathematician Leonard Euler first came up with this. It's easy to assume that i stands for imaginary, merely the truth is, equally with his e, Euler may just accept picked it at random. Whatever the reason, Euler'due south movement has cemented i equally the imaginary number in a very unhelpful way.

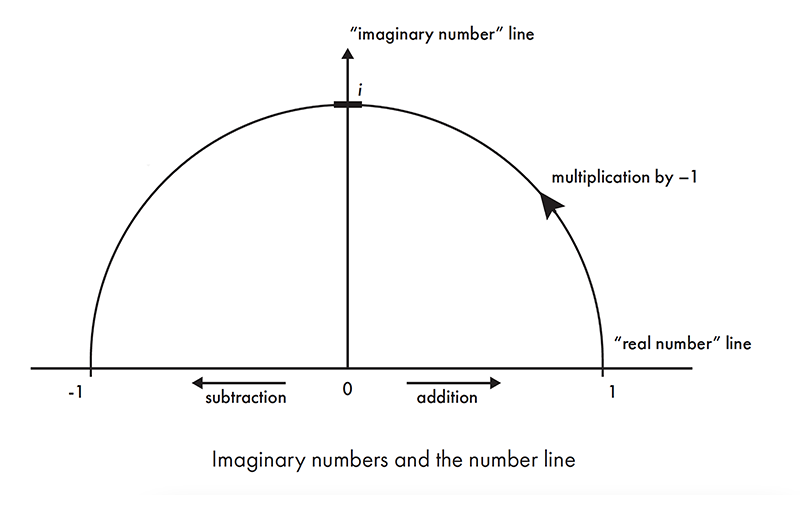

To run into improve what an imaginary number is, let'southward remember of a standard number line that runs from –one to 1 (you can think of it equally a ruler placed on a tabular array in front end of you, running from –1 on the left to +1 on the right). We call the process of moving along the line addition and subtraction (I'chiliad at 0.3, and I'll add 0.3 more than, which takes me to 0.6). Merely nosotros can also imagine making some moves past multiplication. If I get-go at ane, how do I go to –1? I multiply by –i. So let'due south picture multiplication by –1 as half a rotation, anticlockwise, around a circle (in our case, the circle passes through i and –1). It'due south really a rotation by 180 degrees. In mathematicians' preferred units to denote angles, 180 degrees is π radians (360°, a whole circle, is 2π radians).

What happens if we only practice half of this rotation? It's halfway to multiplying by –1, which yous tin can think of as the same as multiplying by √–one. That rotation, by simply π/2 radians (or xc°) leaves our number upward on the top part of the circle's circumference, abroad from the standard number line. And then we can retrieve of the foursquare root of –1 as sitting on a number line that runs at right angles to the number line we're familiar with. It's merely another set of numbers, this fourth dimension on a ruler that meets your other ruler at 90° to class a cantankerous, with +1 at the finish furthest from you, and –1 right in front of you.

That leads united states of america somewhere interesting. The link with rotation in circles ways that i is related to π and the sines and cosines of angles. That relationship is mediated through the foreign number eastward, oftentimes called Euler's number. This "irrational" number begins with the sequence 2.71828… and goes on forever. It is ubiquitous in mathematics and is vital to statistics, calculus, natural logarithms, and a range of arithmetic calculations. Euler worked out exactly what this looks similar by taking a item kind of infinite series (information technology's chosen a Taylor series), and deriving something now known as Euler's formula:

eastward ±iθ = cosθ ± isinθ

This shows at that place is a key human relationship between the base of the natural logarithm and the imaginary number. What's more, you tin reduce this to the relation known as the Euler identity:

due east iπ + one = 0

To some, this is a near-mystical formula. Here nosotros have the base of natural logarithms e; the numbers 0 and 1, which are both unique cases on the whole number line; the imaginary number, a special example all of its ain; and π, which equally we know is a source of power in mathematics. Despite existence discovered at dissimilar times by different people looking at different pieces of mathematics, it turns out they are interrelated, coexisting in this elegant, simple equation.

Seen from a slightly unlike perspective, perhaps nosotros shouldn't be surprised. As with π itself, there really isn't anything mystical nigh this formula. It results from the fact that numbers change and transform themselves and each other through rotations. That only happens because of what numbers are: representations of the relationships between quantities. We don't find anything mystical virtually moving forth the familiar "existent" number line by adding and subtracting. And there's nada dissimilar, really, nigh the transformations that come well-nigh through multiplications and divisions. Remember that sines and cosines are just ratios—1 number divided by some other—that are related to the angles inside triangles, and you can represent those angles as fractions or multiples of π in units known as radians. So what we're discovering here is not some deep mystery most the universe, but a articulate and useful set of relationships that are a event of defining numbers in various different ways.

In fact, these relationships are more than useful—they could be described as vital. Accept their application to science, for example: a full mathematical clarification of nature seems to require imaginary numbers to exist. The "existent" numbers, of which we have learned so much, are not plenty. They must be combined with the imaginary numbers to class the "complex" numbers that Bombelli first created. The result, says mathematician Roger Penrose, is a beautiful abyss. "Complex numbers, as much as reals, and perhaps even more, notice a unity with nature that is truly remarkable," he says in his book The Road to Reality. "It is as though Nature herself is as impressed by the telescopic and consistency of the complex-number system as nosotros are ourselves, and has entrusted to these numbers the precise operations of her world at its minutest scales." In other words, imaginary numbers had to be discovered because they are an essential part of the description of nature.

Michael Brooks is a United Kingdom-based science writer. His nearly contempo volume is The Art of More: How Mathematics Created Civilization.

Excerpted from The Art of More: How Mathematics Created Culture by Michael Brooks. Copyright © 2022 by Michael Brooks. Excerpted by permission of Pantheon Books, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved. No function of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Lead image: agsandrew / Shutterstock

vansicklethestive.blogspot.com

Source: https://nautil.us/imaginary-numbers-are-reality-13999/

Publicar un comentario for "In Everything Real and Imaginary There Is Art and Mathematics"